Sandra (00:03):

My name is Sandra Goss. It’s G O S S rhymes with Moss, but it starts with a G. My thick Southern tongue is frequently not well understood. My age is 57. The date is November 1, 2010, in Knoxville, Tennessee. My pal, Frank Hensley is sitting across the table from me.

Frank (00:24):

My name is Frank Hensley and my age is 77. The date’s November 1, 2010, and we’re located in Knoxville, Tennessee. And I’m, uh, on the board of the Tennessee Citizens for Wilderness Planning along with Sandra Goss, who’s the executive director.

Sandra (00:44):

That’s right. I forgot to say that you’re my boss, too. So Frank, today I thought that we might talk a little bit about you and rivers. I’ve known you now for 12 years, maybe longer. And the first thing I think about, about you is whitewater paddling. Now, tell me a little bit about growing up. Tell me the name of that town in West Virginia and the body of water that you played on there.

Frank (01:15):

Well, I was raised, I’m in a little town, uh, down near the, uh, where Kentucky, Tennessee and Kentucky, uh, West Virginia and Ohio come together, that the town was named, uh, Kenova, K, E, N, O, V, A at, uh, the K E N was for Kentucky and the O for Ohio and the VA for, for Virginia. It was before the, uh, civil war. It was named obviously, and, uh, I was raised there. I spent an awful lot of time on, on the rivers, uh, the Ohio River and the, and the, and the Big Sandy River, which is between West Virginia and Kentucky. And, um, these were just, just beautiful rivers at one time. But, uh,

Sandra (02:05):

Well, wait, just a second. Let’s back up. Why is it obvious that it was before the civil war? Because then it was West Virginia and the, just the Virginia thing on the side of the name of that town again.

Frank (02:17):

Yeah. Kenova, K. E N. O. V. A. And it was, uh, it was, of course, it was the V was for Virginia before the civil war. Right now it’s West by God, Virginia.

Sandra (02:32):

You know, I hadn’t caught onto that. I have trouble remembering the name of that town. I don’t know why. Well, so on this Big Sandy River, is that a big river?

Frank (02:41):

No, it um, it comes out of the, uh, the, there’s two main, uh, uh, tributaries of it, the, um, the Lavasa Fork and the Tug River and they come out of the coalfields of West Virginia and Kentucky and, uh, some of the best, biggest coal reserves in the world really. And, uh, of course, the river was called the Big Sandy for obvious reasons. It had these beautiful big sandbars that would stretch all the way across white sand, but of course they, they had started washing coal in the rivers and uh, and uh, those were turning into, into really coal bars because of all the coal dust in them. But, uh, it was, uh, it was just at one time was just a spectacular river.

Sandra (03:32):

I was kinda surprised to hear you say that it was pretty because I thought there was probably coal damage there, all your growing up time

Frank (03:40):

There, there was it, it had, it had really started and it started, uh, I guess in the 30s, and then I was on the river, uh, in the forties. And, uh, and, uh, it had, uh, it, it, it was still had a lot of white sand, but it, a lot of them, a lot of them had been contaminated with coal, but of course, during the second war, you know, they didn’t really care about pollution. Uh, and, uh, they just, they polluted the river, really bad washing coal. And also there was a big oil refinery on the river and they just dumped everything into the river. It was, it was awful.

Sandra (04:21):

[inaudible] Do you mean they literally washed off the coal?

Frank (04:25):

Yeah, they used to wash coal. Well, they wanted, they used to use cold in, in, uh, in lumps, big lumps, but, but then, uh, they, uh, now, of course, they, they, they, they pulverize it and then they save everything. They actually pulverize it into a dust in the, in the, in the steam plants. So they want everything now, but they used to actually wash it. And, uh, and a lot of those places where they washed it, those big settlement ponds, they’ve gone back and dug the coal out again, dug all that dust out and they use it.

Sandra (05:00):

I’ve got to tell you, my grandparents, heated with coal, big chunks of coal. I never noticed that it was all that clean. I think they might’ve gotten some unwashed coal.

Frank (05:10):

Yeah, they, they washed a lot of coal in the rivers. They just, uh, came in, you know, they had settling ponds, but they were very small and a lot of the, a lot of the coal, a lot what came out was not, not good into the stream.

Sandra (05:23):

Well, so tell me what all you did in the river in terms of, did you swim? Did you ride a boat? Did you fish?

Frank (05:30):

Yeah, I had a boat. Always had a boat and a small Jon boat and a paid $5 for one of them. I remember. But, uh, I’d, I’d swim and we’d swim in the river or sometimes we’d go down to the river and it, uh, it would have oil on it. Uh, and we would, uh, we would dive through the oil slick and come up out in the river and kind of swish it out of the way before we stuck our head it up so we wouldn’t get it in her hair. But, uh, I fished on the river and, uh, we had trot lines and, and uh, and it was, there was still, there was still fish in it, but, uh, it was a, it was a, sadly to say it was, it was going fast. And, uh, and the Ohio river was the same way. Uh, the sewers, all the mains cities, uh, are all, all the cities dump their sewerage directly into the streams. And, uh, there was a lot of, a lot of sewerage, lot of, a lot of contamination back then.

Sandra (06:30):

Was there a lot of, uh, flow change between the seasons on the Big Sandy?

Frank (06:37):

Yeah. All yes, sir. Uh, when the river would get down in the summer when it would, you could walk across those, those, uh, those w what used to be sandbars. You could walk all the way across to almost clear across the river before there was any water, they’d just be a little narrow, narrow, uh, stream coming through the water. And then, uh, the Ohio river, of course, it, it already had some locking dams in it, even in the, in the forties. And so it was some of, uh, the sandbars had been covered up there, but it was still, it was still really beautiful. Uh, but they were, they were, they were building these high high-lift dams at the time and they put those, uh, they put those in in the early sixties, which backed all the water up. Another about another, I guess 20 feet or so and covered up everything, all the sandbars and, and, uh, and, and, and the banks, the river banks where we were used to going.

Sandra (07:41):

Does that mean Big Sandy is now a lake?

Frank (07:44):

Uh, it’s, it’s backwater up. It’s backwater up about, uh, from the Ohio River. It’s backwater up about 20 miles. Yeah.

Sandra (07:52):

How far was the Ohio River from where you lived?

Frank (07:56):

Well, for part of my life, it was just, I could see it. It was just over the hill, except they built floodwalls back out. All the towns back here have flood walls around them. The Corps of Engineers built flood walls to protect the towns. And, uh, and of course it cut the view off of the river. But, uh, you know, it was, uh, you could, I could, it was two city blocks away from my house.

Sandra (08:21):

Wait, what was

Frank (08:22):

the Ohio River? Yeah.

Sandra (08:23):

So you’d go play in the Big Sandy.

Frank (08:26):

Well, we, we lived on a little farm for a while and, uh, and that’s, that’s when I used the Big Sandy River. This was in the late forties, after, after the Second World War. And, uh, and uh, then we moved back where I was used the Ohio River. I used it before we moved to the farm and afterwards.

Sandra (08:48):

What about all this whitewater paddling? How did you get involved in doing that?

Frank (08:55):

Well, when I came down to Tennessee, I just started, uh, hiking on my own around these, around, up in the Big South Fork and, uh, and uh, and the, uh, Big South Fork of the Cumberland River. And, uh, some of the other tributaries of the Tennessee River, the Obed and, and, uh, some of those places. And, and I saw how beautiful it was. I couldn’t believe it really, and how uncontaminated and how pristine some of those places were. And so, um, then I, um, I got me a canoe and, and then I just kind of worked my way into it and on, uh, it wasn’t easy. I had no instruction. And, uh, so I had a, I did a lot of swimming there for a while, but, uh, but I, I would peddle down these streams and they were just, just spectacular. Although there they were beginning to contaminate some of those streams. The Big South Fork of the Cumberland was being, uh, there was some coal, there was a lot of strip mining on it at the time. And, uh, most of that is not, not going on now. Thank goodness.

Sandra (10:05):

You know, all this time I did not realize you were a self-taught paddler.

Frank (10:09):

Yeah, yeah. I hadn’t, I had no formal instruction.

Sandra (10:12):

I get a big kick out of telling people all about your, white water bravery. Are you willing to talk a little bit? I’m recording for posterity, these big o’ scary situations you’ve gotten yourself into and keeping in mind that your wife Catherine, will be listening to this latter.

Frank (10:33):

Well, I used to go by myself a lot now almost all the time I went by myself and I had a little tiny motorcycle, which I would hide on the downstream and, and of the stream. And then I would drive up to the, put in and put my boat in. And, and uh, of course, all this took time. You had to float down and you had to get the motorcycle and ride back to your car and then you had to go back down and get your boat. And all this took time. But one particular time I was, uh, I was, uh, coming down the Obed River and I got to a place that was a fairly rough, it was, matter of fact, it’s, uh, it’s a rated class five rapid and I, uh, got messed up getting into it. So I had to dive out on my boat to keep from going under a rock. So when I dived out, I went too shallow and I hit my, I mean too deep. I’m sorry, too deep. And I hit my chin and knocked two teeth out and busted my chin. And, and uh, of course, I had to go on for the rest of the trip, rod, my motorcycle back to my car.

Sandra (11:49):

All of this with your missing teeth.

Frank (11:54):

Bloody chin. And, and anyway, when I got home finally after all this ordeal, I didn’t want my wife to know about it, so I just hollered and told her I was going to get the emergency room and get a tetanus shot. And so that’s, that’s, that’s pretty much the end of that story. Except she did find out about it when my dentist bill started coming in.

Sandra (12:17):

Well, I think you’d be kind of hard to hide two missing teeth. And going around with your lips really taught over your teeth. Hey, uh, I remember one time you told me, well, I’m not doing any paddling after I’m 70. And this wasn’t last year that you went down the Snake or the Middle Prong or something up in Idaho.

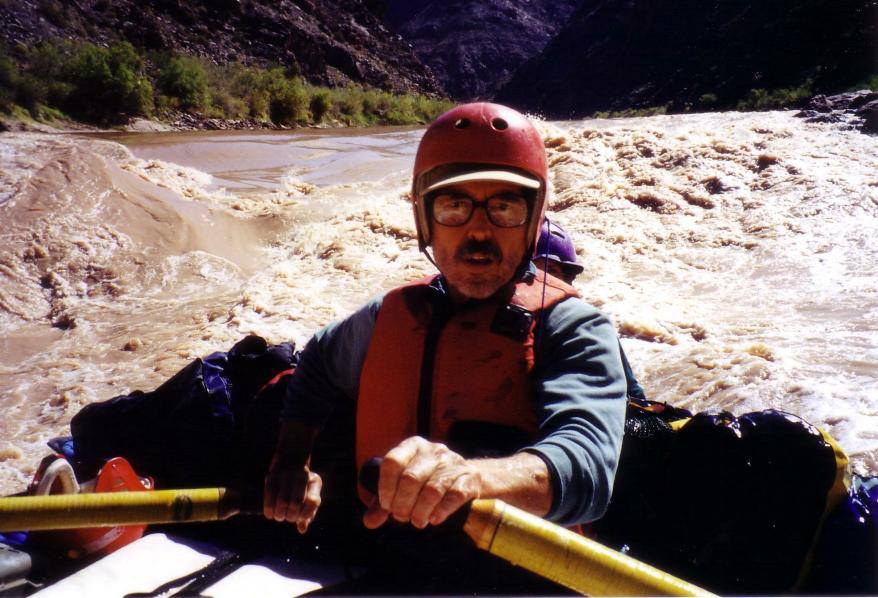

Frank (12:40):

Yeah, we, uh, we went down the, uh, uh, the middle fork of the Salmon River in Idaho. It was, it was really beautiful. Took, uh, took my two daughters with me. It was a commercial trip and they, they were in rafts and then I was in my ducky and, uh, it was, it was like a six day trip. It was really, really great. First time I’d ever really seen that river. And it was, it was just beautiful.

Sandra (13:07):

Well, uh, say a little bit about dirty water, the regulations that had been enacted and enforced over the last several years and if you’ve seen any improvement in the quality of the water.

Frank (13:25):

Well, yeah, I was going back to West Virginia. There’s been a great deal of improvement. Uh, once EPA started coming in in the 60s, they, uh, they made the refineries clean up and, uh, the refineries there had, they had special laws in Kentucky that, uh, they, you know, they didn’t have to meet pollution laws up to that time, but, but EPA put a stop to that. And so the rivers are much cleaner now. Uh, the Ohio River and the Big Sandy River, even though there’s still a lot of contamination from the coalfields and all the strip mining that’s going on, hopefully, that’ll improve I hope in the next few years. But, uh, but the quality of the water is better. Uh, one thing, there’s so many coal barge terminals along that area that you can’t hardly get to the river because they, they load all this coal out of the coalfields and, and well, they loaded from the railroad to barges and, uh, and send it to wherever. You know, they use it. Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, or even overseas. A lot of it goes down to New Orleans is loaded on to ships going over, over, overseas, but too, but the water quality is better then it, then it was when I was a kid.

Sandra (14:46):

Hey, I didn’t know they moved coal on barges. Is it in a wh…they don’t just pile a big old pile of coal on a barge, do they?

Frank (14:55):

Yeah, Yeah. They just loaded in big conveyors and it’s, these barges are huge and apparently it’s much cheaper to send it by river than it is by train. So they, uh, it’s, it’s, it’s unbelievable how much barge traffic is on the Ohio River. It always shocked me that there’s hardly any barge traffic on the Tennessee River, but Ohio River’s just, you can look up and down, see barge traffic anytime you cross, cross the river. Yeah.

Sandra (15:26):

So those barges, they’ve got like pyramids of coal.

Frank (15:30):

Yes. Yeah, they’re about, uh, they’re about eight feet out of the water. There was about, no, there’s about eight feet that, that they go down when they load one of them, they, they sink into the water about eight feet and they’re huge and they hold out, I don’t know how many railroad cars of coal, but they hold a lot of coal.

Sandra (15:54):

Is that just chunks of coal like my grandparents had delivered into their cellar?

Frank (15:58):

No, no. They, they, what they do now, they blend the coal. They blend the coal for the power plant. And, uh, some power plants can burn sulfur coal and others. It depends on the scrubbers and what kind of equipment they have. So they blend it and there’s big blending plants there. And then they loaded into barges and it’s, it’s destined towards certain, certain power plants. And, uh, but it’s, I know there’s no big chunks of coal anymore. It’s all, it’s all, uh, it’s all pulverized to a point where maybe pieces an inch in diameter and then, uh, and then it’s, it’s, it’s farther pulverize when it goes into the, into the boiler. But, uh, no chunks. No.

Sandra (16:47):

I imagine that that business you mentioned early on about the sewage from cities, that’s pretty much a thing of the past all over this country. Thank goodness.

Frank (16:59):

It is. One of the big problems of course here in Tennessee and up there, of course, are the small streams, the small streams, the real small streams are still not protected. And we have that problem right here in Knoxville. And in Oak Ridge we’ve got, uh, we’ve got small streams, Beaver Creek and, and, uh, several, several streams, uh, Bull Run Creek and uh, and, uh, Poplar Creek that still are, are, are not held the way they should be. And of course, that’s, that’s affecting our lakes, you know, and our, and our, I mean, affects our clean water. We need to clean them up.

Speaker 3 (17:47):

And why, can you talk a little bit about what’s the problem with the streams of the small streams?

Frank (17:54):

Well, the small streams, a lot of them, they’re still septic tanks that leak. And, uh, and, and of course we have a, we have a lot of, uh, uh, urban, uh, chemical use and, uh, those pesticides and herbicides and a lot of farm use. And, uh, and that’s, that’s one of the biggest causes of pollution in the streams along with just plain siltation from, uh, front construction projects and, and, and farming.

Sandra (18:30):

Yeah. Let’s not forget, I love to tell everybody who doesn’t pay attention to water quality on a daily basis. Like you and I do. Siltation is our number one water pollutant in this state. And you know, people who don’t follow the issue, they’re very surprised. I think it’s a surprise to them to think that dirt is something that’s inappropriate in the waterway. So I try to tell them, and you help me here if I’ve got this wrong, but I try to tell them, Hey, those fish need a certain amount of water. And the, well, not just the fish, the muscles, all those little aquatic creatures that represent the broad biodiversity we got here. And they need a certain amount of water. And if the water is so dirty, they can’t do their breathing through their gills. They can’t live happy, healthy lives.

Frank (19:28):

Yeah. I’m not a fish expert, but uh, but of course this all this siltation covers the bottom where the, where the, uh, where they lay their eggs, these mayflies and all the different, uh, species that, that the fish feed on you. And it’s not, not a healthy situation at all. As a matter of fact, right now we, you know, the Big South Fork of the Cumberland is a, is a tier three, rated stream, it’s the highest water quality stream, highest water quality that you can, you can have, but still, it has a lot of siltation from, uh, from up on, uh, timbering, timbering going on and strip mining up on New River.

Sandra (20:10):

I don’t think a lot of people realize that. We’ve got two very high-quality bodies of water in the Tennessee area, very close to Knoxville, the Obed, and the Big South Fork. And they’re, they’re nationally, uh, they’re, they’re, they’re of such a quality that they’re nationally ranked as outstanding waters. Tennessee Citizens for Wilderness Planning has done a lot to protect that water quality and uh, be sure that it’s, uh, set aside and part of our work has involved setting aside the lands that border those waters so that they’re protected from development. Other polluting activities.

Frank (21:00):

Yeah, that’s right. And of course, uh, Tennessee Citizens for Wilderness Planning along with other, other organizations work to get the Big South Fork of the Cumberland, which is now a national wildness, a national recreational area, and the Obed, which is in a national wild and scenic river, we work Tennessee Citizens of Wilderness Planning worked to get both of those areas. And, and uh, we still, like you said, we still work to protect them.

Sandra (21:32):

Hey, I heard two things. Well, uh, I’ve actually read two things lately that I haven’t had a chance to mention to you and I thought they were both interesting concepts and one is relevant to the coal ash spill that happened over in Kingston and coal ash and whether it should be designated a hazardous waste, which the EPA is currently considering. Uh, I read this call me just to roughly paraphrase that coal ash is a byproduct that pollutes and we are stuck with that byproduct in part because of the clean air act. So stuff, particulates, and nastiness that the clean air act now prevents from going into the air. We have, as a society, got to deal with that waste. And this writer was making the point that if we don’t watch the coal ash becomes a water-polluting problem. And then let me tell you the second thing I read, I wonder if you read this too. There was a letter to the editor or an op-ed article in the paper suggesting that the New River Valley become a part of the National Park Service.

Frank (22:46):

No, I did not read that. But that, that would be great. A New River, New River. The New River Valley is uh, uh, uh, about, uh, I guess, uh, three-quarters of it is, is, uh, is state-owned land. So the river ought to be part of the, of the Big South Fork National Recreation Area. That’s what should happen. I hope that’s, that does happen.

Sandra (23:13):

So you’re in favor. Oh yeah. And of course, I guess we ought to make it clear, we’re talking about the New River in the upper part of Tennessee. ‘Cause isn’t there a New River up where you came from?

Frank (23:22):

Oh yeah. There’s a New River in West Virginia and it’s a, it’s a, it’s also a beautiful river. It starts in for, it actually starts in North Carolina, comes through Virginia and into West Virginia and then, uh, into the Ohio River there. And it goes into the Kanawha River first and then into the Ohio River. But it’s, it’s a, it’s a, it’s a whitewater’s dream, it’s a, people use a lot. And I used it myself a few weeks ago,

Sandra (23:54):

So now, that, it goes into the Kenova?

Frank (23:57):

Kanawha, Kanawha, yeah. I thought for a second you were saying the name of your town. No, no, it’s the Kanawha River, which goes through, uh, Charleston, West Virginia, which is used to be and still is, a huge chemical producing area. And, um, and uh, of course, it was one time it was really a filthy stream, but now they’ve cleaned it up a lot and it’s, it’s much better too,

Sandra (24:24):

So from starting as a young person, you had a $5 Jon boat and then you went onto a canoe. And I’ve heard you mention a duckie, I’ve been on a raft with you myself and, uh, what, what else do you do? Kayaks?

Frank (24:45):

No, no I don’t, I don’t do any kayak. I cannot just, I might if I was younger, but, uh, I’m too old to start kayaking now.

Sandra (24:55):

Huh? I don’t believe that for a minute. I know that you’ve, uh, I know that you’ve gone on out, you said younger people wouldn’t go on on a bet. Well, so now, Frank, tell me a little bit about you and Catherine, your wife, um, always been kind of tickled about you all knowing one another forever. Was it forever?

Frank (25:21):

Well, yeah, I knew her. I knew her for part of the time in high school. I moved to out to the farm and, but then, um, I knew her, I knew her in high school, you know, and, uh, and then when I got out of the service in 19, uh, in 1955, uh, we got married a year later, 1956. And, uh, and we decided that we would go to California. I was, I was working on a municipal fire department and we decided we’d go to California where all the money was and

Sandra (26:01):

cause you didn’t have any money where you were.

Frank (26:03):

Right. So we went out there and spent, uh, spent, uh, three years and I went to school at night and then came back in 1960. And, uh, and, um, went to Marshall University and graduated in engineering and, and uh, and three years later came to Tennessee. So been there since 1967.

Sandra (26:26):

So did you do any boating in California?

Frank (26:28):

No, no. did not, did not have time to vote in California. No.

Speaker 3 (26:33):

What brought you to Tennessee?

Frank (26:37):

Uh, well there was a, I answered a job advertisement in the Cincinnati paper for, uh, for the government plants at, uh, at, uh, Oak Ridge.

Sandra (26:48):

And so what kind of engineer are you?

Frank (26:50):

Mechanical engineer. Machine design. Machine design engineer. Where did you go to school? Marshall. Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia.

Sandra (27:01):

Did you get the Cincinnati paper over there in Marshall, West Virginia? And I’m kind of ignorant about my geography. How far is that?

Frank (27:11):

Oh, it’s 120 miles I guess. But uh, yeah, they, you could get to all the papers. Yeah.

Sandra (27:17):

Oh, it’s just 120 miles. I don’t want to talk bad about West Virginia, but I always think of it as kind of remote and hard to get to and not really on the way to anywhere.

Frank (27:28):

Well, it has the same area code for the whole state. One of the only States in the United States, I guess. But yeah, still.

Sandra (27:43):

Oh, well, I’m pretty right then and I bet you there isn’t a state left that’s like that.

Frank (27:49):

Right, but it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s a beautiful state. Uh, it has, uh, it has some of the most beautiful country of any state in the United States. And it’s the part that, that I was from was probably the most polluted part of it on up in the state. It was really beautiful and pristine. And now there’s a lot of mining going on, but, uh, but still it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s a beautiful place, although in the, on some of the tributaries of the Big Sandy River, it’s, there’s some awful strip mining going on and, uh, some big battles right now, the filling of those streams up there, those small streams. And I’m hoping that’s going to stop. But, uh, it’s a beautiful state

Speaker 3 (28:42):

For the people, because this is on audio. So for somebody who has never been to some of the most beautiful places in West Virginia, how would you, would you like to describe them? Well, what do they look like?

Frank (28:54):

Well, of course, the New River Valley is one of the most is, is, is a wonderful, beautiful place. It’s one of the oldest rivers in the world. Uh, I think it, it and the Nile River are the two oldest rivers in the world. And, uh, it cut, it cut through that, those, those coal seams and know all that strata up there. And it’s just, it’s just a beautiful Canyon. Of course, back in the 20s, they dammed it. And a part of the lower part of it then used ran a, water through an eight-mile tunnel down to a powerhouse. But, uh, but the, but on above that, it’s, it’s really a beautiful stream. And then if, if, uh, an a and a beautiful Canyon, and then if you’re going up in West Virginia into the Monongahela National Forest and all that area, it’s, it’s really beautiful. There are ski areas up in there and, uh, and, uh, it’s, it’s just a wonderful, wonderful place to go.

Sandra (29:56):

Are those canyons, do they have trees on them?

Frank (29:59):

Yes. Yes. So they’re not, they’re not vertical cliffs like out in the Grand Canyon, but uh, yes, they do have trees on all their, all forest and all those,

Sandra (30:11):

Are they deciduous trees or evergreens?

Frank (30:15):

Er, both?

Sandra (30:16):

So, is there a pretty view of the fall colors up there in the fall?

Frank (30:20):

Yes. Wonderful. Wonderful. Yes.

Sandra (30:24):

What are the roads like?

Frank (30:25):

The roads are good. The roads in West Virginia are just really, really good. They’ve, uh, they’ve had, um, they’ve had a lot of road building. They have the, one of the, uh, uh, I believe the highest bridge in the United States, uh, across New River, Rainbow Bridge. And of course one day a year they closed the bridge and all the crazy guys go out there and jump off of it, you know.

Sandra (30:52):

Do they let the crazy girls go too?

Frank (30:53):

Yeah, Oh, Yeah. Crazy…

Sandra (30:54):

Let’s not be sexist about our crazy opportunities, that’s not nice?

Frank (30:58):

No. You can be either sex can be crazy.

Sandra (31:04):

So, you jump off on a bungee cord?

Frank (31:05):

Jump off and parachutes so those. Uh, yeah,

Sandra (31:12):

I might want to do that! Do they touch the water?

New Speaker (31:12):

No, no. They usually land. Well, some of them have touched the water. Yeah. But they usually land are some, there are some, there are some gravel bars and down, down below and sandbars. And they land on those

.

Sandra (31:25):

You know, give it a choice. I think I’d rather lay it in the water than on a gravel bar, that sounds ouchy.

Frank (31:31):

Well, the water’s moving pretty fast there. So you’d be better if you landed on land.

Sandra (31:36):

Oh, what time of year does that happen?

Frank (31:41):

It’s in the, it’s in a, it’s in, uh, September. Yeah, the latter part of September.

Sandra (31:49):

It could be the newest TCWP outing. Well, Frank about this, a whitewater paddling business. Do you have a big trip planned up here in the next several months that will take you to some exciting whitewater?

Frank (32:07):

No, no, we don’t have anything. I have, um, I have a trip on the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon, uh, to go row my own boat there and the next October, which will probably be my last trip there, it’d be the third trip. And uh, but it’s a private trip and uh, you have to wait a long time to get a private trip., about 12 years.

Sandra (32:31):

Oh, I might note, your other two trips were probably the last time you’d ever do them too, so I’m not putting any stock in that. So next October you’re going to be going down to Colorado. That’s sounds kind of exciting.

Frank (32:46):

It is exciting. Yeah.

Speaker 3 (32:48):

And what do you mean when it’s a private trip? What does that mean?

Frank (32:51):

That means that you furnish everything. You furnish your boats and get your boats, and you cook all your meals and, and uh, you, you do everything. It’s uh, you know, normally people go down, they hire, uh, these commercial outfits and they take them down. But you do everything. And on the Grand Canyon, everything you take in, you got to carry out. Everything!

Sandra (33:17):

That includes human waste, just in case anybody’s wondering.

Frank (33:19):

Human waste, ashes out of your fire. You have to have a firebox. You carry everything out. And uh, and that makes it so that it’s really a pristine place. Even with all the people that use it, they’ve done a really good job.

Speaker 3 (33:34):

And why have you picked that, that trip and that location to be, or what you call your last trip that Sandra seems skeptical? So why, why, why did you want to go?

Frank (33:44):

Well, it’s so hard. It’s a beautiful, first off, it’s a mile, a mile deep in the ground. And, uh, and also it’s very hard to get, it’s very hard to get a, uh, a trip. There you have to go. Now they have a lottery system and uh, and before it took this particular trip, it’s taken 12 years. Uh, the guy applied for 12 years ago. So it takes a long time even with the lottery system, the new lottery system. So it’s, but it’s just such a wonderful place. You know, when you start down and you can’t, the only way out is 225 miles by river. So, uh, it’s really a spectacular trip.

Sandra (34:28):

I know from being with you, uh, in the, on the Big South Fork that the views and the grandeur of what one sees going down the river is nothing that you get to see looking at the overlooks or even hiking. Uh, and I envy you going down the Grand Canyon on the, on the Colorado. Not enough to want to go with you.

Frank (35:01):

Yeah. The only way to see it is from the water.

Sandra (35:04):

Yeah. Well, for anybody that’s thinking they might want to become a paddler, you got any words of wisdom?

Frank (35:12):

Uh, join a club, join a paddling club and, and uh, and learn, learn to do it. They’ll teach you and then you can, uh, enjoy. You can enjoy your weekends on the river.

Speaker 3 (35:24):

So you’re advising them to not do what you did, which was to teach yourself?

Frank (35:29):

No, I don’t advise teaching, teaching yourself. No.

Sandra (35:34):

Plus I think over the years since you started paddling equipment has changed quite a bit. And is it improved in terms of safety?

Frank (35:45):

Yes. And yeah, and, and it’s also the new whitewater paddlers runs rapids that used to be classified as unrideable. So they do all the waterfalls. And so the things they do nowadays just would have been impossible 20 years ago.

Sandra (36:10):

Uh, I used to go down the Hiawassee River again in Tennessee on an inner tube. Oh, went down it dozens of times on an inner tube. I sent word to some old pals, Hey, we need to go down in the Hiwassee next summer on inner tubes, kind of revisit our youth. And I got a message back. Oh no, inner tubes are old ha and they told me the name of something that I can’t quite recall, but even inner tubes evidently are improved. So there’s dozens of improvement on, on water activities. Well Frank, I am so delighted that we’ve had this opportunity to chat a little bit. It’s always fun and interesting to hear your comments and your stories about what all you’ve been into.

Frank (36:56):

Yeah, I’m, I’m, I’m glad to, to tell a little bit of it, but I guess the most important thing is, is our water quality. And I just hope, uh, hope we keep improving it, not to let it get back like it was. And that’s the most important thing.

Speaker 3 (37:15):

Why, why is that the most important thing? Why is that the most important thing in your opinion?

Frank (37:21):

Well, because water is, is we all need water and, and, uh, and, and, and, and these herbicides and pesticides that contaminate it. And, and, and it is really, in my opinion, terrible that we do this to our streams because, uh, when they test a water, there’s always a level of pesticides, level of herbicides in them, other chemicals. So I really think that we’ll find that this is affecting our health. And, uh, it’s just very important in my opinion, that we, that we keep, that we clean up our streams.

Sandra (38:08):

Well, that is a lovely positive note to end our talk on. And I might observe that not only are we faced with herbicides, fertilizers, pesticides, and other things, but you know, prescription medicines, hormones that are involved in feeding animals.

Frank (38:28):

That’s a big problem, yes.

Sandra (38:30):

There’s more and more coming to light about how humans and they’re testing us and finding that we are ingesting these things and the jury is still out on what the effect on our health is from those things. But clearly it is affecting our human health.

Frank (38:49):

It is a problem that’s for sure. From these big feedlots where they, they use all these antibiotics on the, for the cattle. Yes. That’s a really big problem.

Sandra (39:03):

Okay, well thanks, Frank.

Frank (39:04):

Than you.